Arthropods (/ˈɑːrθrəpɒd/ ARTH-rə-pod)[3] are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (metameric) segments, and paired jointed appendages. In order to keep growing, they must go through stages of moulting, a process by which they shed their exoskeleton to reveal a new one. They form an extremely diverse group of up to ten million species.

Haemolymph is the analogue of blood for most arthropods. An arthropod has an open circulatory system, with a body cavity called a haemocoel through which haemolymph circulates to the interior organs. Like their exteriors, the internal organs of arthropods are generally built of repeated segments. They have ladder-like nervous systems, with paired ventral nerve cords running through all segments and forming paired ganglia in each segment. Their heads are formed by fusion of varying numbers of segments, and their brains are formed by fusion of the ganglia of these segments and encircle the esophagus. The respiratory and excretory systems of arthropods vary, depending as much on their environment as on the subphylum to which they belong.

Arthropods use combinations of compound eyes and pigment-pit ocelli for vision. In most species, the ocelli can only detect the direction from which light is coming, and the compound eyes are the main source of information, but the main eyes of spiders are ocelli that can form images and, in a few cases, can swivel to track prey. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many bristles known as setae that project through their cuticles. Similarly, their reproduction and development are varied; all terrestrial species use internal fertilization, but this is sometimes by indirect transfer of the sperm via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection. Aquatic species use either internal or external fertilization. Almost all arthropods lay eggs, with many species giving birth to live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother; but a few are genuinely viviparous, such as aphids. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillars that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis to produce the adult form. The level of maternal care for hatchlings varies from nonexistent to the prolonged care provided by social insects.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralians (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa. Overall, however, the basal relationships of animals are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated. Today, arthropods contribute to the human food supply both directly as food, and more importantly, indirectly as pollinators of crops. Some species are known to spread severe disease to humans, livestock, and crops.

Etymology

[edit]

The word arthropod comes from the Greek ἄρθρον árthron ‘joint‘, and πούς pous (gen. ποδός podos) ‘foot‘ or ‘leg‘, which together mean “jointed leg”,[4] with the word “arthropodes” initially used in anatomical descriptions by Barthélemy Charles Joseph Dumortier published in 1832.[1] The designation “Arthropoda” appears to have been first used in 1843 by the German zoologist Johann Ludwig Christian Gravenhorst (1777–1857).[5][1] The origin of the name has been the subject of considerable confusion, with credit often given erroneously to Pierre André Latreille or Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold instead, among various others.[1]

Terrestrial arthropods are often called bugs.[Note 1] The term is also occasionally extended to colloquial names for freshwater or marine crustaceans (e.g., Balmain bug, Moreton Bay bug, mudbug) and used by physicians and bacteriologists for disease-causing germs (e.g., superbugs),[8] but entomologists reserve this term for a narrow category of “true bugs“, insects of the order Hemiptera.[8]

Description

[edit]

Arthropods are invertebrates with segmented bodies and jointed limbs.[9] The exoskeleton or cuticles consists of chitin, a polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine.[10] The cuticle of many crustaceans, beetle mites, the clades Penetini and Archaeoglenini inside the beetle subfamily Phrenapatinae,[11] and millipedes (except for bristly millipedes) is also biomineralized with calcium carbonate. Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occur in some opiliones,[12] and the pupal cuticle of the fly Bactrocera dorsalis contains calcium phosphate.[13]

Diversity

[edit]

Arthropoda is the largest animal phylum, with the estimates of the number of arthropod species varying from 1,170,000 to 5~10 million and accounting for over 80 percent of all known living animal species.[14][15] One arthropod sub-group, the insects, includes more described species than any other taxonomic class.[16] The total number of species remains difficult to determine. This is due to the census modeling assumptions projected onto other regions in order to scale up from counts at specific locations applied to the whole world. A study in 1992 estimated that there were 500,000 species of animals and plants in Costa Rica alone, of which 365,000 were arthropods.[16]

They are important members of marine, freshwater, land and air ecosystems and one of only two major animal groups that have adapted to life in dry environments; the other is amniotes, whose living members are reptiles, birds and mammals.[17] Both the smallest and largest arthropods are crustaceans. The smallest belong to the class Tantulocarida, some of which are less than 100 micrometres (0.0039 in) long.[18] The largest are species in the class Malacostraca, with the legs of the Japanese spider crab potentially spanning up to 4 metres (13 ft)[19] and the American lobster reaching weights over 20 kg (44 lbs).

Segmentation

[edit]

_______________________

_______________________

_______________________

Segments and tagmata of an arthropod[17]

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The last common ancestor of living arthropods probably consisted of a series of undifferentiated segments, each with a pair of appendages that functioned as limbs. However, all known living and fossil arthropods have grouped segments into tagmata in which segments and their limbs are specialized in various ways.[17]

The three-part appearance of many insect bodies and the two-part appearance of spiders is a result of this grouping.[21] There are no external signs of segmentation in mites.[17] Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an ocular somite at the front, where the mouth and eyes originated,[17][22] and a telson at the rear, behind the anus.

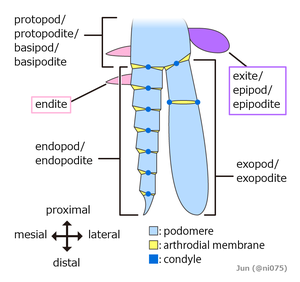

Originally, it seems that each appendage-bearing segment had two separate pairs of appendages: an upper, unsegmented exite and a lower, segmented endopod. These would later fuse into a single pair of biramous appendages united by a basal segment (protopod or basipod), with the upper branch acting as a gill while the lower branch was used for locomotion.[23][24][20] The appendages of most crustaceans and some extinct taxa such as trilobites have another segmented branch known as exopods, but whether these structures have a single origin remain controversial.[25][26][20] In some segments of all known arthropods, the appendages have been modified, for example to form gills, mouth-parts, antennae for collecting information,[21] or claws for grasping;[27] arthropods are “like Swiss Army knives, each equipped with a unique set of specialized tools.”[17] In many arthropods, appendages have vanished from some regions of the body; it is particularly common for abdominal appendages to have disappeared or be highly modified.[17]

0: ● Ocular somite

1-2…: ∎ Somites of head tagma (head / cephalon / prosoma)

…7-10: ∎ Abdominal somites (further somites omitted)

P: ∎ Protocerebral somite / appendage

D: ∎ Deutocerebral somite / appendage

T: ∎ Tritocerebral somite / appendage

L: ∎ Walking leg / abdomen

†: Extinct taxa

Alignment of anterior body segments and appendages across various arthropod taxa, based on the observations until the mid 2010s. Head regions in black.[22][28]

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata (sea spiders, horseshoe crabs and arachnids), Myriapoda (symphylans, pauropods, millipedes and centipedes), Pancrustacea (oligostracans, copepods, malacostracans, branchiopods, hexapods, etc.), and the extinct Trilobita – have heads formed of various combinations of segments, with appendages that are missing or specialized in different ways.[17][28] Despite myriapods and hexapods both having similar head combinations, hexapods are deeply nested within crustacea while myriapods are not, so these traits are believed to have evolved separately. In addition, some extinct arthropods, such as Marrella, belong to none of these groups, as their heads are formed by their own particular combinations of segments and specialized appendages.[29]

Working out the evolutionary stages by which all these different combinations could have appeared is so difficult that it has long been known as “The arthropod head problem“.[30] In 1960, R. E. Snodgrass even hoped it would not be solved, as he found trying to work out solutions to be fun.[Note 2]

Exoskeleton

[edit]

Main article: Arthropod exoskeleton

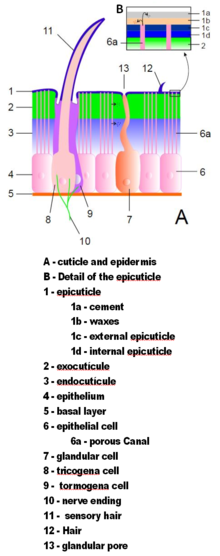

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of cuticle, a non-cellular material secreted by the epidermis.[17] Their cuticles vary in the details of their structure, but generally consist of three main layers: the epicuticle, a thin outer waxy coat that moisture-proofs the other layers and gives them some protection; the exocuticle, which consists of chitin and chemically hardened proteins; and the endocuticle, which consists of chitin and unhardened proteins. The exocuticle and endocuticle together are known as the procuticle.[32] Each body segment and limb section is encased in hardened cuticle. The joints between body segments and between limb sections are covered by flexible cuticle.[17]

The exoskeletons of most aquatic crustaceans are biomineralized with calcium carbonate extracted from the water. Some terrestrial crustaceans have developed means of storing the mineral, since on land they cannot rely on a steady supply of dissolved calcium carbonate.[33] Biomineralization generally affects the exocuticle and the outer part of the endocuticle.[32] Two recent hypotheses about the evolution of biomineralization in arthropods and other groups of animals propose that it provides tougher defensive armor,[34] and that it allows animals to grow larger and stronger by providing more rigid skeletons;[35] and in either case a mineral-organic composite exoskeleton is cheaper to build than an all-organic one of comparable strength.[35][36]

The cuticle may have setae (bristles) growing from special cells in the epidermis. Setae are as varied in form and function as appendages. For example, they are often used as sensors to detect air or water currents, or contact with objects; aquatic arthropods use feather-like setae to increase the surface area of swimming appendages and to filter food particles out of water; aquatic insects, which are air-breathers, use thick felt-like coats of setae to trap air, extending the time they can spend under water; heavy, rigid setae serve as defensive spines.[17]

Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, some still use hydraulic pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors;[37] for example, all spiders extend their legs hydraulically and can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level.[38]

Moulting

[edit]

Main article: Ecdysis

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton, the exuviae, after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.[39]

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle and thus detaches the old cuticle. This phase begins when the epidermis has secreted a new epicuticle to protect it from the enzymes, and the epidermis secretes the new exocuticle while the old cuticle is detaching. When this stage is complete, the animal makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air, and this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the old exocuticle was thinnest. It commonly takes several minutes for the animal to struggle out of the old cuticle. At this point, the new one is wrinkled and so soft that the animal cannot support itself and finds it very difficult to move, and the new endocuticle has not yet formed. The animal continues to pump itself up to stretch the new cuticle as much as possible, then hardens the new exocuticle and eliminates the excess air or water. By the end of this phase, the new endocuticle has formed. Many arthropods then eat the discarded cuticle to reclaim its materials.[39]

Because arthropods are unprotected and nearly immobilized until the new cuticle has hardened, they are in danger both of being trapped in the old cuticle and of being attacked by predators. Moulting may be responsible for 80 to 90% of all arthropod deaths.[39]

Internal organs

[edit]

= heart

= gut

= brain / ganglia

O = eye

Basic arthropod body structure

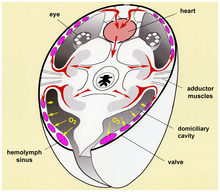

Arthropod bodies are also segmented internally, and the nervous, muscular, circulatory, and excretory systems have repeated components.[17] Arthropods come from a lineage of animals that have a coelom, a membrane-lined cavity between the gut and the body wall that accommodates the internal organs. The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom’s main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton, which muscles compress in order to change the animal’s shape and thus enable it to move. Hence the coelom of the arthropod is reduced to small areas around the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood flows.[40]

Respiration and circulation

[edit]

See also: Hemolymph and hemocyte

Arthropods have open circulatory systems. Most have a few short, open-ended arteries. In chelicerates and crustaceans, the blood carries oxygen to the tissues, while hexapods use a separate system of tracheae. Many crustaceans and a few chelicerates and tracheates use respiratory pigments to assist oxygen transport. The most common respiratory pigment in arthropods is copper-based hemocyanin; this is used by many crustaceans and a few centipedes. A few crustaceans and insects use iron-based hemoglobin, the respiratory pigment used by vertebrates. As with other invertebrates, the respiratory pigments of those arthropods that have them are generally dissolved in the blood and rarely enclosed in corpuscles as they are in vertebrates.[40]

The heart is a muscular tube that runs just under the back and for most of the length of the hemocoel. It contracts in ripples that run from rear to front, pushing blood forwards. Sections not being squeezed by the heart muscle are expanded either by elastic ligaments or by small muscles, in either case connecting the heart to the body wall. Along the heart run a series of paired ostia, non-return valves that allow blood to enter the heart but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front.[40]

Arthropods have a wide variety of respiratory systems. Small species often do not have any, since their high ratio of surface area to volume enables simple diffusion through the body surface to supply enough oxygen. Crustacea usually have gills that are modified appendages. Many arachnids have book lungs.[41] Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnids.[42]

Nervous system

[edit]

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of ganglia from which sensory and motor nerves run to other parts of the segment. Although the pairs of ganglia in each segment often appear physically fused, they are connected by commissures (relatively large bundles of nerves), which give arthropod nervous systems a characteristic ladder-like appearance. The brain is in the head, encircling and mainly above the esophagus. It consists of the fused ganglia of the acron and one or two of the foremost segments that form the head – a total of three pairs of ganglia in most arthropods, but only two in chelicerates, which do not have antennae or the ganglion connected to them. The ganglia of other head segments are often close to the brain and function as part of it. In insects, these other head ganglia combine into a pair of subesophageal ganglia, under and behind the esophagus. Spiders take this process a step further, as all the segmental ganglia are incorporated into the subesophageal ganglia, which occupy most of the space in the cephalothorax (front “super-segment”).[43]

Excretory system

[edit]

There are two different types of arthropod excretory systems. In aquatic arthropods, the end-product of biochemical reactions that metabolise nitrogen is ammonia, which is so toxic that it needs to be diluted as much as possible with water. The ammonia is then eliminated via any permeable membrane, mainly through the gills.[41] All crustaceans use this system, and its high consumption of water may be responsible for the relative lack of success of crustaceans as land animals.[44] Various groups of terrestrial arthropods have independently developed a different system: the end-product of nitrogen metabolism is uric acid, which can be excreted as dry material; the Malpighian tubule system filters the uric acid and other nitrogenous waste out of the blood in the hemocoel, and dumps these materials into the hindgut, from which they are expelled as feces.[44] Most aquatic arthropods and some terrestrial ones also have organs called nephridia (“little kidneys“), which extract other wastes for excretion as urine.[44]

Senses

[edit]

The stiff cuticles of arthropods would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly setae, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste and smell, often by means of setae. Pressure sensors often take the form of membranes that function as eardrums, but are connected directly to nerves rather than to auditory ossicles. The antennae of most hexapods include sensor packages that monitor humidity, moisture and temperature.[45]

Most arthropods lack balance and acceleration sensors, and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. The self-righting behavior of cockroaches is triggered when pressure sensors on the underside of the feet report no pressure. However, many malacostracan crustaceans have statocysts, which provide the same sort of information as the balance and motion sensors of the vertebrate inner ear.[45]

The proprioceptors of arthropods, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well understood. However, little is known about what other internal sensors arthropods may have.[45]

Optical

[edit]

Main article: Arthropod eye

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of compound eyes and pigment-cup ocelli (“little eyes”). In most cases, ocelli are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, the main eyes of spiders are pigment-cup ocelli that are capable of forming images,[45] and those of jumping spiders can rotate to track prey.[46]

Compound eyes consist of fifteen to several thousand independent ommatidia, columns that are usually hexagonal in cross section. Each ommatidium is an independent sensor, with its own light-sensitive cells and often with its own lens and cornea.[45] Compound eyes have a wide field of view, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light.[47] On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within 20 cm (8 in) are most important to most arthropods.[45] Several arthropods have color vision, and that of some insects has been studied in detail; for example, the ommatidia of bees contain receptors for both green and ultra-violet.[45]

Olfaction

[edit]

Further information: Insect olfaction

Reproduction and development

[edit]

Aphid giving birth to live young from an unfertilized egg

Harvestmen mating

A few arthropods, such as barnacles, are hermaphroditic, that is, each can have the organs of both sexes. However, individuals of most species remain of one sex their entire lives.[48] A few species of insects and crustaceans can reproduce by parthenogenesis, especially if conditions favor a “population explosion”. However, most arthropods rely on sexual reproduction, and parthenogenetic species often revert to sexual reproduction when conditions become less favorable.[49] The ability to undergo meiosis is widespread among arthropods including both those that reproduce sexually and those that reproduce parthenogenetically.[50] Although meiosis is a major characteristic of arthropods, understanding of its fundamental adaptive benefit has long been regarded as an unresolved problem,[51] that appears to have remained unsettled.

Aquatic arthropods may breed by external fertilization, as for example horseshoe crabs do,[52] or by internal fertilization, where the ova remain in the female’s body and the sperm must somehow be inserted. All known terrestrial arthropods use internal fertilization. Opiliones (harvestmen), millipedes, and some crustaceans use modified appendages such as gonopods or penises to transfer the sperm directly to the female. However, most male terrestrial arthropods produce spermatophores, waterproof packets of sperm, which the females take into their bodies. A few such species rely on females to find spermatophores that have already been deposited on the ground, but in most cases males only deposit spermatophores when complex courtship rituals look likely to be successful.[48]

Most arthropods lay eggs,[48] but scorpions are ovoviviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care.[53] Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or caterpillars, which do not have segmented limbs or hardened cuticles, and metamorphose into adult forms by entering an inactive phase in which the larval tissues are broken down and re-used to build the adult body.[54] Dragonfly larvae have the typical cuticles and jointed limbs of arthropods but are flightless water-breathers with extendable jaws.[55] Crustaceans commonly hatch as tiny nauplius larvae that have only three segments and pairs of appendages.[48]

Evolutionary history

[edit]

See also: Phylogeny of insects

Last common ancestor

[edit]

Based on the distribution of shared plesiomorphic features in extant and fossil taxa, the last common ancestor of all arthropods is inferred to have been as a modular organism with each module covered by its own sclerite (armor plate) and bearing a pair of biramous limbs.[56] However, whether the ancestral limb was uniramous or biramous is far from a settled debate. This Ur-arthropod had a ventral mouth, pre-oral antennae and dorsal eyes at the front of the body. It was assumed to have been a non-discriminatory sediment feeder, processing whatever sediment came its way for food,[56] but fossil findings hint that the last common ancestor of both arthropods and Priapulida shared the same specialized mouth apparatus: a circular mouth with rings of teeth used for capturing animal prey.[57]

Fossil record

[edit]

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals Parvancorina and Spriggina, from around 555 million years ago, were arthropods,[58][59][60] but later study shows that their affinities of being origin of arthropods are not reliable.[61] Small arthropods with bivalve-like shells have been found in Early Cambrian fossil beds dating 541 to 539 million years ago in China and Australia.[62][63][64][65] The earliest Cambrian trilobite fossils are about 520 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and worldwide, suggesting that they had been around for quite some time.[66] In the Maotianshan shales, which date back to 518 million years ago, arthropods such as Kylinxia and Erratus have been found that seem to represent transitional fossils between stem (e.g. Radiodonta such as Anomalocaris) and true arthropods.[67][68][24] Re-examination in the 1970s of the Burgess Shale fossils from about 505 million years ago identified many arthropods, some of which could not be assigned to any of the well-known groups, and thus intensified the debate about the Cambrian explosion.[69][70][71] A fossil of Marrella from the Burgess Shale has provided the earliest clear evidence of moulting.[72]

The earliest fossil of likely pancrustacean larvae date from about 514 million years ago in the Cambrian, followed by unique taxa like Yicaris and Wujicaris.[73] The purported pancrustacean/crustacean affinity of some cambrian arthropods (e.g. Phosphatocopina, Bradoriida and Hymenocarine taxa like waptiids)[74][75][76] were disputed by subsequent studies, as they might branch before the mandibulate crown-group.[73] Within the pancrustacean crown-group, only Malacostraca, Branchiopoda and Pentastomida have Cambrian fossil records.[73] Crustacean fossils are common from the Ordovician period onwards.[77] They have remained almost entirely aquatic, possibly because they never developed excretory systems that conserve water.[44]

Arthropods provide the earliest identifiable fossils of land animals, from about 419 million years ago in the Late Silurian,[41] and terrestrial tracks from about 450 million years ago appear to have been made by arthropods.[78] Arthropods possessed attributes that were easy coopted for life on land; their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.[79] Around the same time the aquatic, scorpion-like eurypterids became the largest ever arthropods, some as long as 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in).[80]

The oldest known arachnid is the trigonotarbid Palaeotarbus jerami, from about 420 million years ago in the Silurian period.[81][Note 3] Attercopus fimbriunguis, from 386 million years ago in the Devonian period, bears the earliest known silk-producing spigots, but its lack of spinnerets means it was not one of the true spiders,[83] which first appear in the Late Carboniferous over 299 million years ago.[84] The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods provide a large number of fossil spiders, including representatives of many modern families.[85] The oldest known scorpion is Dolichophonus, dated back to 436 million years ago.[86] Lots of Silurian and Devonian scorpions were previously thought to be gill-breathing, hence the idea that scorpions were primitively aquatic and evolved air-breathing book lungs later on.[87] However subsequent studies reveal most of them lacking reliable evidence for an aquatic lifestyle,[88] while exceptional aquatic taxa (e.g. Waeringoscorpio) most likely derived from terrestrial scorpion ancestors.[89]

The oldest fossil record of hexapod is obscure, as most of the candidates are poorly preserved and their hexapod affinities had been disputed. An iconic example is the Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti, dated at 396 to 407 million years ago, its mandibles are thought to be a type found only in winged insects, which suggests that the earliest insects appeared in the Silurian period.[90] However later study shows that Rhyniognatha most likely represent a myriapod, not even a hexapod.[91] The unequivocal oldest known hexapod is the springtail Rhyniella, from about 410 million years ago in the Devonian period, and the palaeodictyopteran Delitzschala bitterfeldensis, from about 325 million years ago in the Carboniferous period, respectively.[91] The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about 300 million years ago, include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivores, detritivores and insectivores. Social termites and ants first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic.[92]

External phylogeny

[edit]

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist Sidnie Manton and others argued that arthropods are polyphyletic, in other words, that they do not share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod. Instead, they proposed that three separate groups of “arthropods” evolved separately from common worm-like ancestors: the chelicerates, including spiders and scorpions; the crustaceans; and the uniramia, consisting of onychophorans, myriapods and hexapods. These arguments usually bypassed trilobites, as the evolutionary relationships of this class were unclear. Proponents of polyphyly argued the following: that the similarities between these groups are the results of convergent evolution, as natural consequences of having rigid, segmented exoskeletons; that the three groups use different chemical means of hardening the cuticle; that there were significant differences in the construction of their compound eyes; that it is hard to see how such different configurations of segments and appendages in the head could have evolved from the same ancestor; and that crustaceans have biramous limbs with separate gill and leg branches, while the other two groups have uniramous limbs in which the single branch serves as a leg.[94]

| onychophorans includes Aysheaia and Peripatus armored lobopodsincludes Hallucigenia and Microdictyondinocarids (s.l.)anomalocarid-includes modern tardigrades as well as extinct animals like Kerygmachela and Opabinialike taxa (s.l.)anomalocarids (s.s.)Anomalocarisarthropodsincludes living groups and extinct forms such as trilobites | |

Simplified summary of Budd’s (1996) “broad-scale” cladogram[93]

Further analysis and discoveries in the 1990s reversed this view, and led to acceptance that arthropods are monophyletic, in other words they are inferred to share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod.[95][96] For example, Graham Budd‘s analyses of Kerygmachela in 1993 and of Opabinia in 1996 convinced him that these animals were similar to onychophorans and to various Early Cambrian “lobopods“, and he presented an “evolutionary family tree” that showed these as “aunts” and “cousins” of all arthropods.[93][97] These changes made the scope of the term “arthropod” unclear, and Claus Nielsen proposed that the wider group should be labelled “Panarthropoda” (“all the arthropods”) while the animals with jointed limbs and hardened cuticles should be called “Euarthropoda” (“true arthropods”).[98]

A contrary view was presented in 2003, when Jan Bergström and Hou Xian-guang argued that, if arthropods were a “sister-group” to any of the anomalocarids, they must have lost and then re-evolved features that were well-developed in the anomalocarids. The earliest known arthropods ate mud in order to extract food particles from it, and possessed variable numbers of segments with unspecialized appendages that functioned as both gills and legs. Anomalocarids were, by the standards of the time, huge and sophisticated predators with specialized mouths and grasping appendages, fixed numbers of segments some of which were specialized, tail fins, and gills that were very different from those of arthropods. In 2006, they suggested that arthropods were more closely related to lobopods and tardigrades than to anomalocarids.[99] In 2014, it was found that tardigrades were more closely related to arthropods than velvet worms.[100]

| Protostomes | Spiralia (annelids, molluscs, brachiopods, chaetognatha, etc.) EcdysozoaNematoida (nematodes and close relatives) Scalidophora (priapulids and Kinorhyncha, and Loricifera) PanarthropodaOnychophorans TactopodaTardigrades EuarthropodaChelicerates Mandibulata†Euthycarcinoids Myriapods PancrustaceaCrustaceans Hexapods | |

| Relationships of Ecdysozoa to each other and to annelids, etc.,[101][failed verification] including euthycarcinoids[102] | ||

Higher up the “family tree”, the Annelida have traditionally been considered the closest relatives of the Panarthropoda, since both groups have segmented bodies, and the combination of these groups was labelled Articulata. There had been competing proposals that arthropods were closely related to other groups such as nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades, but these remained minority views because it was difficult to specify in detail the relationships between these groups.

In the 1990s, molecular phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences produced a coherent scheme showing arthropods as members of a superphylum labelled Ecdysozoa (“animals that moult”), which contained nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades but excluded annelids. This was backed up by studies of the anatomy and development of these animals, which showed that many of the features that supported the Articulata hypothesis showed significant differences between annelids and the earliest Panarthropods in their details, and some were hardly present at all in arthropods. This hypothesis groups annelids with molluscs and brachiopods in another superphylum, Lophotrochozoa.

If the Ecdysozoa hypothesis is correct, then segmentation of arthropods and annelids either has evolved convergently or has been inherited from a much older ancestor and subsequently lost in several other lineages, such as the non-arthropod members of the Ecdysozoa.[103][101]

Internal phylogeny

[edit]

Early arthropods

[edit]

Further information: Deuteropoda

| Arthropod fossil phylogeny[104] |

| Arthropodagiant lobopodians †gilled lobopodians †Radiodonta †DeuteropodaChelicerataMegacheira †Artiopoda †Isoxyida †Mandibulata |

| Summarized cladogram of the relationships between extinct arthropod groups. For more, see Deuteropoda. |

Aside from the four major living groups (crustaceans, chelicerates, myriapods and hexapods), a number of fossil forms, mostly from the early Cambrian period, are difficult to place taxonomically, either from lack of obvious affinity to any of the main groups or from clear affinity to several of them. Marrella was the first one to be recognized as significantly different from the well-known groups.[29]

Modern interpretations of the basal, extinct stem-group of Arthropoda recognised the following groups, from most basal to most crownward:[105][104]

- The “Giant” or “Siberiid Lobopodians”, such as Jianshanopodia, Siberion and Megadictyon, are the most basal grade in the total-group Arthropoda.

- The “Gilled Lobopodians”, such as Kerygmachela, Pambdelurion and Opabinia, are the second most basal grade.

- The Radiodonta, which traditionally known as anomalocaridids come in third position, and are thought to be monophyletic.

- A possible “upper stem-group” assemblage of more uncertain position[104] but contained within Deuteropoda:[105] the Fuxianhuiida, Megacheira, and multiple “bivalved forms” including Isoxyida and Hymenocarina.

The Deuteropoda is a recently established clade uniting the crown-group (living) arthropods with these possible “upper stem-group” fossils taxa.[105] The clade is defined by important changes to the structure of the head region such as the appearance of a differentiated deutocerebral appendage pair, which excludes more basal taxa like radiodonts and “gilled lobopodians”.[105]

Controversies remain about the positions of various extinct arthropod groups. Some studies recover Megacheira as closely related to chelicerates, while others recover them as outside the group containing Chelicerate and Mandibulata as stem-group euarthropods.[106] The placement of the Artiopoda (which contains the extinct trilobites and similar forms) is also a frequent subject of dispute.[107] The main hypotheses position them in the clade Arachnomorpha with the Chelicerates. However, one of the newer hypotheses is that the chelicerae have originated from the same pair of appendages that evolved into antennae in the ancestors of Mandibulata, which would place trilobites, which had antennae, closer to Mandibulata than Chelicerata, in the clade Antennulata.[106][108] The fuxianhuiids, usually suggested to be stem-group arthropods, have been suggested to be Mandibulates in some recent studies.[106] The Hymenocarina, a group of bivalved arthropods, previously thought to have been stem-group members of the group, have been demonstrated to be mandibulates based on the presence of mandibles.[104]

- Radiodonts, Opabiniids, Gilled Lobopodians and the more traditional Lobopodians are all examples of basal stem-group arthropod lineages from the Cambrian

- Anomalocaris

(Radiodonta) - Opabinia

(Opabiniidae) - Kerygmachela

(Kerygmachelidae) - Facivermis

(Luolishaniidae)

- Marrellomorphs, megacherians, funxianhuiids and phosphatocopines are some examples of Cambrian arthropods whose classification remains difficult

- Marrella

(Marrellomorpha) - Leanchoilia

(Megacheira) - Fuxianhuia

(Fuxianhuiida) - Dabashanella

(Phosphatocopina)

- Other examples of now extinct arthropod groups include

- Acutiramus

(Eurypterida) - Apankura

(Euthycarcinoidea) - Trimerus

(Artiopoda) - Concavicaris

(Thylacocephala)

List of arthropod groups and genera († denotes extinct taxa)

- “Dinocaridida” † (generally considered paraphyletic,[109] sometimes treated as lobopodians)

- Kerygmachelidae †[109]

- Pambdelurion † (possible lobopodian)[106]

- Mieridduryn † (possible opabiniid)[110]

- Parvibellus † (possible “Siberiid Lobopodian”)[111]

- Opabiniidae †[109]

- Radiodonta †[109]

- Cucumericrus † (possible radiodont)

- Caryosyntrips † (possible radiodont)

- Bradoriida †[112]

- Deuteropoda[109]

- Artiopoda †[106]

- Trilobita †[113]

- Agnostida (possibly trilobites)[114] †

- Nektaspida †[113]

- Aglaspidida †[113]

- Cheloniellida †[113]

- Bushizheia †[115]

- Erratus[116] †

- Fengzhengia[117] †

- Fuxianhuiida †[113]

- Isoxyida †[118]

- Kiisortoqia †[119]

- Kylinxia[68] †

- Marrellomorpha †[120]

- Megacheira † (possibly paraphyletic, alternatively placed as stem-chelicerates)[121]

- Chelicerata[106]

- Habeliida †[106]

- Pycnogonida

- Prosomapoda

- “Synziphosurina” (paraphyletic)

- Xiphosura

- Dekatriata[122]

- Phosphatocopina (possible stem mandibulate)[123] †

- Mandibulata[106]

- Artiopoda †[106]

- Incertae sedis

- Aaveqaspis[129] †

- Arthrogyrinus[130] †

- Bennettarthra [131] †

- Cambropachycopidae[132] †

- Cambropodus[133] †

- Camptophyllia[134] †

- Chuandianella[135] †

- Notchia[136] †

- Burgessia[137] †

- Parioscorpio[138] †

- Pleuralata[139] †

- Rhynimonstrum [140] †

- Sarotrocercus[141] †

- Strabopida[142] †

- Wingertshellicus[143] †

- Zhenghecaris[144] †

Living arthropods

[edit]

See also: List of arthropod orders

The phylum Arthropoda is typically subdivided into four subphyla, of which one is extinct:[145]

- Artiopods are an extinct group of formerly numerous marine arthropods that disappeared in the Permian–Triassic extinction event, though they were in decline prior to this killing blow, having been reduced to a handful of orders in the Late Devonian extinction.[146] They contain groups such as the trilobites, nektaspids, aglaspidids, and the cheloniellids among others.

- Chelicerates comprise the marine sea spiders and horseshoe crabs, along with the terrestrial arachnids such as mites, harvestmen, spiders, scorpions and related organisms characterized by the presence of chelicerae, appendages just above/in front of the mouthparts. Chelicerae appear in scorpions and horseshoe crabs as tiny claws that they use in feeding, but those of spiders have developed as fangs that inject venom.

- Myriapods comprise millipedes, centipedes, pauropods and symphylans, characterized by having numerous body segments each of which bearing one or two pairs of legs (or in a few cases being legless). All members are exclusively terrestrial.

- Pancrustaceans comprise ostracods, barnacles, copepods, malacostracans, cephalocaridans, branchiopods, remipedes and hexapods. Most groups are primarily aquatic (two notable exceptions being woodlice and hexapods, which are both purely terrestrial) and are characterized by having biramous appendages. The most abundant group of pancrustaceans are the terrestrial hexapods, which comprise insects, diplurans, springtails, and proturans, with six thoracic legs.

The phylogeny of the major extant arthropod groups has been an area of considerable interest and dispute.[147] Recent studies strongly suggest that Crustacea, as traditionally defined, is paraphyletic, with Hexapoda having evolved from within it,[148][149] so that Crustacea and Hexapoda form a clade, Pancrustacea. The position of Myriapoda, Chelicerata and Pancrustacea remains unclear as of April 2012. In some studies, Myriapoda is grouped with Chelicerata (forming Myriochelata);[150][151] in other studies, Myriapoda is grouped with Pancrustacea (forming Mandibulata),[148] or Myriapoda may be sister to Chelicerata plus Pancrustacea.[149]

The following cladogram shows the internal relationships between all the living classes of arthropods as of the late 2010s,[152][153][154] as well as the estimated timing for some of the clades:[155]

| Arthropoda | ChelicerataPycnogonidaProsomapodaXiphosuraArachnidaMandibulataMyriapodaChilopodaSymphylaDignathaPauropodaDiplopodaPancrustaceaOligostracaOstracodaMystacocaridaIchthyostracaAltocrustaceaMulticrustaceaCopepodaMalacostracaTantulocaridaThecostracaAllotriocaridaCephalocaridaAthalassocaridaBranchiopodaLabiocaridaRemipediaHexapodaEllipluraCollembolaProturaCercophoraDipluraInsecta440 mya470 mya493 mya | CrustaceansEntognaths |

Interaction with humans

[edit]

Main article: Arthropods in culture

See also: Insects as food

Crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns have long been part of human cuisine, and are now raised commercially.[156] Insects and their grubs are at least as nutritious as meat, and are eaten both raw and cooked in many cultures, though not most European, Hindu, and Islamic cultures.[157][158] Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia,[159][160][161] and by the Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela, after the highly irritant hairs – the spider’s main defense system – are removed.[162] Humans also unintentionally eat arthropods in other foods,[163] and food safety regulations lay down acceptable contamination levels for different kinds of food material.[Note 4][Note 5] The intentional cultivation of arthropods and other small animals for human food, referred to as minilivestock, is now emerging in animal husbandry as an ecologically sound concept.[167] Commercial butterfly breeding provides Lepidoptera stock to butterfly conservatories, educational exhibits, schools, research facilities, and cultural events.

However, the greatest contribution of arthropods to human food supply is by pollination: a 2008 study examined the 100 crops that FAO lists as grown for food, and estimated pollination’s economic value as €153 billion, or 9.5 per cent of the value of world agricultural production used for human food in 2005.[168] Besides pollinating, bees produce honey, which is the basis of a rapidly growing industry and international trade.[169]

The red dye cochineal, produced from a Central American species of insect, was economically important to the Aztecs and Mayans.[170] While the region was under Spanish control, it became Mexico‘s second most-lucrative export,[171] and is now regaining some of the ground it lost to synthetic competitors.[172] Shellac, a resin secreted by a species of insect native to southern Asia, was historically used in great quantities for many applications in which it has mostly been replaced by synthetic resins, but it is still used in woodworking and as a food additive. The blood of horseshoe crabs contains a clotting agent, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate, which is now used to test that antibiotics and kidney machines are free of dangerous bacteria, and to detect spinal meningitis. Forensic entomology uses evidence provided by arthropods to establish the time and sometimes the place of death of a human, and in some cases the cause.[173] Recently insects have also gained attention as potential sources of drugs and other medicinal substances.[174]

The relative simplicity of the arthropods’ body plan, allowing them to move on a variety of surfaces both on land and in water, have made them useful as models for robotics. The redundancy provided by segments allows arthropods and biomimetic robots to move normally even with damaged or lost appendages.[175][176]

| Disease[177] | Insect | Cases per year | Deaths per year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | Anopheles mosquito | 267 M | 1 to 2 M |

| Dengue fever | Aedes mosquito | 5 M | 5,000 |

| Yellow fever | Aedes mosquito | 4,432 | 1,177 |

| Filariasis | Culex mosquito | 250 M | unknown |

Although arthropods are the most numerous phylum on Earth, and thousands of arthropod species are venomous, they inflict relatively few serious bites and stings on humans. Far more serious are the effects on humans of diseases like malaria carried by blood-sucking insects. Other blood-sucking insects infect livestock with diseases that kill many animals and greatly reduce the usefulness of others.[177] Ticks can cause tick paralysis and several parasite-borne diseases in humans.[178] A few of the closely related mites also infest humans, causing intense itching,[179] and others cause allergic diseases, including hay fever, asthma, and eczema.[180]

Many species of arthropods, principally insects but also mites, are agricultural and forest pests.[181][182] The mite Varroa destructor has become the largest single problem faced by beekeepers worldwide.[183] Efforts to control arthropod pests by large-scale use of pesticides have caused long-term effects on human health and on biodiversity.[184] Increasing arthropod resistance to pesticides has led to the development of integrated pest management using a wide range of measures including biological control.[181] Predatory mites may be useful in controlling some mite pests.[185][186]